By Alan Murdie

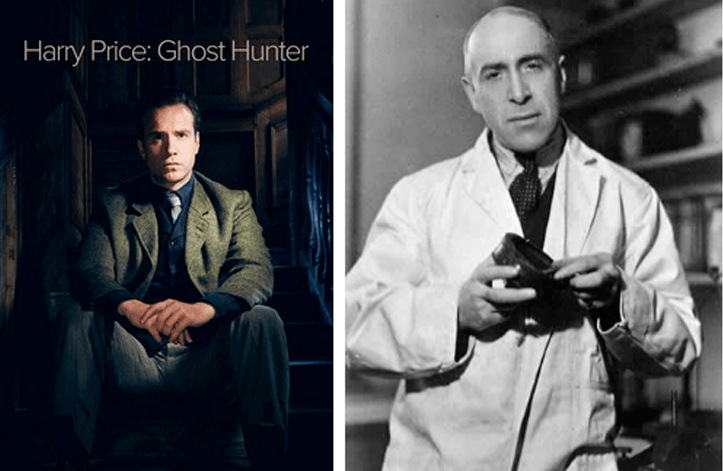

That you can’t libel the dead is well-known. It will have been ghost hunters and TV viewers who care for historical accuracy Harry Price – Ghost Hunter, a one-off drama broadcast ITV1 in the UK on 27 December 2015 who will have disappointed, if not offended but there’s no cause of action for that. Inspired by the novel The Ghost Hunters (2013) by Neil Spring about Price at Borley Rectory, it was billed as a ‘spine chilling mix of real history, fiction and the famous legend of Harry Price’.[1] Regrettably, this one-off drama presented an extremely misleading depiction of the personality of the man who was the best known psychical researcher of the twentieth century, an internationally regarded figure, who produced an immense output of published work and was among the first to recognise the value of Charles Fort.[2] Were Price alive today he would have been more than justified in bringing defamation proceedings. Based on what I saw on screen within the first ten minutes, I would have been happy to represent him.

Harry Price (1881-1948) has been both championed and vilified as a psychic investigator in the seventy years since his death. Regrettably this drama had virtually nothing to do with Price’s real 20 year investigation of Borley Rectory ‘the most haunted house in England’, the actual theme of Neil Spring’s book. Instead, it based itself around a wholly invented tale which sends Price investigating an alleged haunting in the country manor owned by a fictitious Liberal politician named Goodwin who was secretly trying to drive his wife mad by poisoning her with barbiturates (a plot partly derived from the film Gaslight (1944)). Goodwin is jealously reacting to his adulterous wife having become pregnant by a former handy man, only to lose the baby later (events having a faint echo with allegations concerning Marianne Foyster wife of the Revd. Lionel Foyster, incumbent at Borley between 1930-35)[3]. Along the way Price challenges a fraudulent medium revered by the mother of the Goodwins’s housemaid who assists him.

From a legal angle, the most blatant perversion of fact for me – aside from falsely suggesting Price’s wife was a mental patient – were opening scenes showing Price faking séance effects to extract money from a gullible family. Another scene featured a similarly duped soldier committing suicide on Price’s front doorstep. Thus, Price was presented as the perpetrator of acts which would constitute criminal offences both then and now, and would amount to libels without further proof of damage if Price was living. [4] Aside from the fact neither event ever happened, it was a complete distortion to depict Price posing as a spiritualist. In fact, this was one thing even his harshest sceptical critics could never accuse him of doing.

The real Harry Price was a Christian and highly sceptical of Spiritualism

The real Harry Price was initially a hard-baked sceptic, and throughout his life he considered mediumistic effects were mostly fraudulent. He was a man no more likely to hold a phoney spiritualist séance than Richard Dawkins would be likely to lead a prayer meeting. A committed member of the Church of England, he had a profound contempt for hosts of fraudulent mediums who exploited the grief of the bereaved after World War I. He exposed many frauds and was often very scathing towards gullible spiritualists, some of whom he categorised as ‘Cheese-Cloth Worshippers’.[5] His biographer Paul Tabori styled him ‘the whipping boy of spiritualism’ stating “the rites and trappings of spiritualist churches awakened a deep antipathy which of he never rid himself.”[6] He had many critics amongst spiritualists and stirred up furious controversy, clashing often with Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. But it was not until after Price’s death in March 1948 that anyone was openly prepared to call his integrity and honesty into question in the way this television presumed at the outset.

Attacks commenced nine months after his death. In December 1948 a Daily Mail journalist named Charles Sutton claimed he had apprehended Price with his with pockets “full of bricks and pebbles” faking a stone-throwing poltergeist at Borley Rectory in 1929.[7] More serious was the sceptical The Haunting of Borley Rectory (1956) by Eric Dingwall, Kathleen Goldney, both of whom had worked with Price, and Trevor Hall, who never met him but displayed an extraordinary hostility towards his memory. Their book sought to demolish the case for ghosts at Borley, with Hall proving the most persistent critic, single-handedly repeating his attacks in further books such as New Light on Old Ghosts (1966) and an entire critical biography The Search for Harry Price (1978).

Books vilifying Harry Price appeared in 1978 and 2001 but give a partial view

If you wish to read Price’s faults exhaustively dissected, Hall’s books provide or suggest them all. Price is condemned for distorting and disguising his working class background, for his lack of advanced education, for exploiting psychical research financially, of being careless with facts, for slips of memory, for borrowing library books and not returning them, for faking or allowing dubious or naturally occurring phenomena to be passed off as paranormal, together with suspicions of literal skull-duggery with an allegation of planting human remains in the burnt-out rectory cellar at Borley in 1943.[8]

That Hall was a man obsessed with the case is clear in his zealous pursuit of the aforementioned Marianne Foyster of Borley. But for those 18 months of alleged poltergeist activity she would have been wholly forgotten; Price suspected much but certainly did not know all of her sexual antics when he published his first Borley book The Most Haunted House in England (1940), 11 years into the case which was to occupy him for 20 years until his death.

Borley Rectory, the ‘haunted house’ which was to occupy Price for twenty years

For Hall, Marianne to some extent replaced Price as a fixation, pursuing her across the Atlantic after she left Britain as a GI bride in 1945. In his spare time he compiled a 600 page dossier on her life and lovers, gloatingly presenting her as a scheming nymphomaniac, bigamously married several times over and even a potential murderess. However, a psychiatrist he enlisted in 1980 for his exposure pulled out of his pet project and in the end Hall was robbed of his triumph of publishing an expose by pre-deceasing Marianne, by then long-settled in Canada in 1992 by a year. Subsequently, an anaemic version of Hall’s dossier published by Robert Wood, as The Widow of Borley in 1993, the year she died. Since then the leading book devoted to attacking Price was appeared in 2001 as Harry Price – Psychic Detective revisiting many of the allegations, and correcting a number of Hall’s errors.[9]

However, in my view the damage to Price’s reputation was ultimately done not by any of these books – which have themselves been the subject of challenge argument and rejoinder[10] – but repetition of the tide of abuse and exaggerated language they released among reviewers working for influential and high-brow publications. For example, The Economist branded Price “a rogue, a falsifier and manufacturer of evidence” whilst The Observer declared of Price’s Borley books ‘Not one brick in the whole extraordinary fabric of suggestion, muddle-mindedness, gullibility and publicity-hunting remains on another‘. [11] Not only did these broad-brush smears damage the reputation of Price but they opened the door to subsequent waves of denigration of other psychical researchers,[12] and spanning the generations they have eventually filtered down to commercial television giving us Harry Price – Ghost Hunter.

Ghost Club member Robert Aickman who knew Price and visited Borley

Amid such loaded language the person who has regard for the truth must tread more carefully. Price was no saint and certainly had his faults and flaws but a more balanced view came from Robert Aickman who knew Price declared him neither as good, nor as bad as people made out. Another who knew him was Dennis Bardens, the founder of the BBC’s Panorama programme who was also impressed. [13]

To this extent the biggest mistake of the ITV dramatists and many who consider him today is to see Price primarily as a ghost hunter. What one can certainly say is that the case that has been presented against Price into the 21st century has been curiously, indeed obsessively one-sided, proceeding far more by way of innuendo than direct evidence, focusing on Borley and avoiding consideration of his laboratory work.

Admittedly, Price wrote an autobiographical work entitled Confessions of A Ghost Hunter (1936) but only a quarter of the book is dedicated exploring the haunted houses and poltergeists. In reality, Price spent far more time in séance rooms and laboratories– particularly in the 1920s and early 1930s testing mediums applying controlled conditions than visiting haunted houses. Price was primarily a gadgets man,[14] interested in practical ways of testing mediums; he was not in any sense a theoretician or interested in the psychological aspects of mediumship.[15] Despite mediums claiming communication with them dead Price saw them as generating a physical force unknown to science and craved recognition as a scientist.

Three series of experiments stand out. Price extensively tested the telekinetic powers a young English woman, Stella Cranshaw, attracting much attention at the time but swiftly forgotten. His results were finally issued in book form in 1973, edited by James Turner (who had bought the site of Borley Rectory in 1946) but it attracted little attention.[16]

Price also joined in international research efforts into Eleonore Zugun, a Romanian teenager surrounded by poltergeist effects, conducting extensive tests with her in London in 1927.[17] Even more remarkable was his decade-long research into the Austrian Schneider brothers, a pair of teenage mediums between 1922-1932. Price brought Rudi Schneider to London for 100 sittings attended by numerous independent observers, rushing out an entire book soon after,[18] similarly forgotten today. Ultimately, it was Price himself who undermined his own work when in a fit of pique in 1933 he released a single photograph implying Rudi might have cheated at one session. This came after Rudi opted to go to Paris with other researchers whom Price saw as rivals.[19] Price Critics have avoided this research, merely alleging fraud without explaining how it was done, why dozens of other people involved themselves and, more crucially, just why researchers reported similar experimental findings in independent tests.

The Rudi Schneider incident shows Price’s great failing was his ego, being obsessed with publicity and showmanship, leading to numerous superficial stunts at haunted houses duly adored by the public. His greatest interest in phenomena outside the laboratory was not actually ghosts but poltergeists, one shared with Charles Fort because of their physical and potentially measurable aspects. In appreciating the labours of Fort, Price was an exception at the time. Like Charles Fort, Price also assiduously collected newspaper stories – 25,000 of them about himself. [20]

Finally, it is minor and carping to point out that Rafe Spall was ludicrously miscast as the eponymous lead character. Price was neither slim nor good-looking, rather ‘bald-headed, short and stocky’[21] as photographs confirm. Price was not isolated as depicted, though neither did he possess marked social charm or have the ability to mix well (“he had no small talk” [22]). Altogether Price was engrossed in his work to the point of obsession and “very sensitive to being found in error”.[23] His friend Sidney Glanville further detailed this sensitivity: ‘[h]e was the last man to sit down under any criticism, especially if he had the slightest idea that it was unjustified – perhaps even if it was!”[24] whilst Paul Tabori recalled him “as a hot-tempered, impetuous man” and that ‘Those of us who knew him could easily testify that he could and did lose his temper quickly and gloriously” – one who if he had ever been accused of fraud in life would have “reacted with a punch on the nose rather than some meek muttering”.[25]

So much for Harry Price, but what can be pleaded for his fictional treatment of Price in the ITV show?

The introduction real characters into wholly fictional stories can be an entertaining device and a way of exploring new ideas and theories about the past. Equally, it can be symptomatic of mere laziness or a paucity of creative imagination on the part of writers. More pertinently, the duress of feeding the demands of the modern entertainment economy, today’s generation of dramatists no longer enjoy the luxuries of generous budgets or time to wade through numerous out-of-print books and archives to ensure their facts are right. Truth is swiftly sacrificed for entertainment purposes, as dramatists choose to freely invent whilst original authors relinquish control.[26] More pertinently, lengthy rounds of laboratory tests and experimental sittings don’t make for prime-time drama.

2016 also sees ITV Encore channel airing Houdini and Doyle which has Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and Harry Houdini teamed up for a set of adventures which never happened. If facts don’t matter, why not throw in a few ‘Lost World’ dinosaurs as well?

REFERENCES

[1] ITV Press announcement 13 July 2015; writer Jack Lothian, Bentley Productions

[2] Price, Harry (1945) Poltergeist Over England. Country Life Books.

[3] See Tabori, Paul and Underwood, Peter(1973) in The Ghosts of Borley (1973)David & Charles; Wood, Robert (1993) The Widow of Borley. Duckworth; Adams, Paul, Brazil, Eddie and Underwood, Peter (2009) The Borley Companion. History Press.

[4] Fraud, theft, the Vagrancy Act 1824 and the Fraudulent Mediums Act 1951 and the Consumer Protection Regulations 2008 all come to mind.

[5] Price, Harry (1933) Leaves from a Psychist’s Case-Book. Gollancz.

[6] Tabori, Paul (1950, 1974) Harry Price Ghost Hunter Chapter 4 p63.

[7] Sutton, Charles (1948) The Inky Way Annual No 2; see The Borley Rectory Companion (2009)by Paul Adams, Eddie Brazil and Peter Underwood and discussion in The Ghosts of Borley (1973) by Paul Tabori and Peter Underwood pp 97-106.

[8] Hall, Trevor (1978) The Search for Harry Price. Duckworth. See also the entry for Hall in The Borley Companion note 7

[9] Morris, Richard (2006) Harry Price – The Psychic Detective. History Press.

[10] Randall, John L. (2000) ] Harry Price: the Case for the Defence in Journal of the SPR July 2000.

[11] Published in 1956 and quoted in Hall, Trevor (1966) New Light On Old Ghosts. Duckworth.

[12] Hastings, Robert The Borley Report. Society for Psychical Research 1969, p. 77.

[13] Aickman, Robert (1966) Introduction 2nd Fontana Book of Great Ghost Stories; Dennis Bardens personal communication 2000.

[14] Meeker, Lucy formerly Mrs Lucy Kaye In Tabori note 6 p282-285

[15] Tabori, Paul note 5

[16] Turner, James / Price, Harry (1973). Stella C.. An account of some original experiments in psychical research. Record of sittings with a physical medium. Souvenir Press. Reviewed by Anita Gregory, Journal of the SPR vol 47, 1973, pp. 265-7.

[17] Price, Harry (1926) ‘Poltergeist Phenomena of Eleonore Zugun’ Journal of the American SPR p 459.

[18] Price, Harry (1930) Rudi Schneide: A Scientific Examination of his Mediumshir; : Gregory, Anita (1985) ) The Strange case of Rudi Schneider. Scarecrow Press Gregory, Anita (1977) in Annals of Science vol 34 pp 449-559; Hope, Lord (1932) ‘Report of a series of sittings with Rudi Schneider’. Proceedings of the SPR vol 41 255-330.

[19] Gregory, Anita (1987) Gregory, Anita. Anatomy of a Fraud reviewed by Alan Gauld, Journal 49, 1978, pp. 828-35.

[20] Tabori, Paul op cit. p.35

[21] Turner, James (1973) introduction Stella C. p.

[22] Meeker, Lucy formerly Mrs Lucy Kaye In Tabori p284-285

[23] Glanville, Sidney in Tabori. Paul note 7 at p. 275

[24] Glanville, Sidney in letter to Peter Underwood 2 September 1950, cited Tabori and Underwood (1973) n.7.

[25] Tabori, Paul and Underwood, Peter (1973) in The Ghosts of Borley note 3.

[26] As Neil Spring states ‘ once you have sold the dramatic rights to your work, it is your professional duty to stand back and let the producers, directors and actors do their work’. Guardian 14 Dec 2015.

First Published in Fortean Times, 2016