The 1st of July 2016 marks the 100th anniversary of the start of the Battle of the Somme, one of the deadliest battles of the First World War. Along with Verdun in France, and Flanders in Belgium, the Somme was the scene of one of the greatest losses of human life on the Western Front and the place where the British Army suffered its greatest number of casualties in one day.

That relatively few ghost experiences have been reported around the Somme, Verdun and the battlefields of Flanders in the century since has long been something of a puzzle and a source of speculation and debate, although I suspect that accounts may await discovery in the vast literature of the conflict and memoirs of those who served. But perhaps inevitably – because of the associations – many have felt a sense of presence at these places which seems to intensify as the years go on. The battlefields of the Somme and the Western front now attract far more visitors than thirty years ago.

Certainly local guides with whom I spoke on a tour of sites in Flanders with the Ghost Club in September 2014 had heard no ghost stories, but some intriguing fragments were picked up at Ypres by a BBC News Magazine journalist Chris Haslam, close to Remembrance Sunday that year. In the course of researching a discussion piece entitled, “Does the WW1 tourist trade exploit the memory of the fallen?” he states:

“My disquiet is caused by something less solid – a brooding sense of malevolence oozing from the earth, as though the violence has a half-life. I’m no believer in spooks but the old lady I meet walking her dachshund most certainly is. Her name is Beatrijs and her dog is called Robert. As we amble down the muddy track, she tells me about mysterious lights seen flickering in no man’s land, of half-heard screams in the night and of corners of fields where generations of Robert’s ancestors have refused to go.”

(BBC News Magazine November 9 2014 at http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-29930997.

Yet the relative lack of apparition reports at the Somme and other First World War battle sites remains a puzzle. The answer may be that (1) (traditional) ghosts are spirits of the dead but because rites and rituals have venerated them they no longer haunt; (2) ghosts are not souls of the dead but place memories and there has been too much disruption to ground which might be presumed to receive recordings (presuming there is something in ‘place memory’ theory of ghosts as recordings ; (3) the sites of these battlefields and the cemeteries around them are effectively vast graveyards, and graveyards are surprisingly unhaunted ;(4) the scale of the death and destruction is on such a scale that no single apparitional experience can be generated, effectively blotting out individual psychic echoes. Essentially many ghost encounters seem to relate to individual rather than to collective deaths and trauma and perhaps personal psychic traces are lost, leaving just an ‘atmosphere’. But we simply don’t know, and the possibility that such experiences may be socially and culturally is a factor to consider.

Certainly at the time, World War I did generate an enormous number of ghostly experiences, though largely on an individual rather than collective level (the story of the Angel of Mons has been discredited as simply a modern legend).

Perhaps the most impressive visionary experience of ghostly figures claimed was that by James Wentworth Day of witnessing phantom French and German cavalry re-enacting a skirmish from the early days of 1914. Day witnessed this in November 1918 at Bailleul, Flanders, describing his experience in his Here are Ghosts and Witches (1954) and his last book on hauntings Essex Ghosts (1974). Given Day’s pronounced tendencies for weaving ripping yarns and his role as enthusiastic propagandist for ghostly folklore (sometimes dreaming up fictitious local characters for dramatic effect) one might be suspicious that this episode was an exercise in imaginative writing. But he named a fellow witness, a Corporal Jock Barr of Glasgow, and from the circumstantial details he provided it is possible to pin-point the location to a precise hilltop.

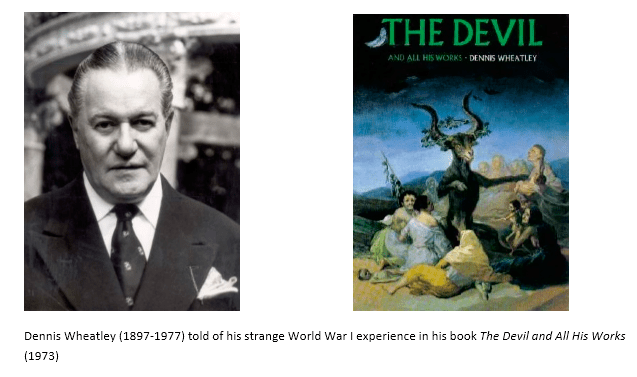

DENNIS WHEATLEY AND THE ‘ELEMENTAL’

But such stories are an exception. Rather than see apparitions, the one connecting experience between soldiers of the time and visitors of today is the sense of a presence, sometimes malign. The conflict has not left individual ghosts but an intangible feeling on the places where so many perished. Such impressions would have made sense to novelist and supernatural thriller writer Dennis Wheatley (1897-1977) who served as a soldier on the Western Front in the war. In a story he told to the Ghost Club and in his book The Devil and All His Works (1973) cites as his own personal experience resting after the Battle of Cambrai. He and group of fellow officers commandeered a ruined mansion that had been occupied by the Germans and still contained discarded blood-stained uniforms. As they were intending to stay some months, Wheatley decided to erect a mess himself, laying bricks which had been specially cleaned by his soldier servant. Conditions meant Wheatley had to work alone after dark, until one night he was suddenly overwhelmed by total panic and fled the scene of his building project. He wrote, “I am convinced I was attacked by an elemental”. In occult lore, an elemental is a non-human spirit or demon attracted to sites of death and suffering and Wheatley was a believer in black magic.

THE ELEMENTAL OF THIEPVAL WOOD?

William Orpen’s painting of the Somme Battlefield where he encountered a strange force

A similar experience seems to have befallen the painter and official war artist William Orpen at the Somme some 18 months after the commencement of the battle.

In November 1917, Orpen was painting in Thiepval Wood. Today Thiepval has a monument dedicated to the missing of the Somme. Carved upon it are the names of 73,367 British and Commonwealth soldiers, who have no known grave. In November 1917 many bodies still lay unburied and though more than a years since fighting had ceased in the area it was still scattered with human remains. The artist felt a strange sense of presence which persisted. After he had already been painting for a couple of hours, ‘the sun was still shining, but the day seemed dark. Orpen was overwhelmed by feelings of dread and fear. Sitting by the shattered trunk of a blackened tree, something seemed to suddenly seemed to rush at him. He could see nothing but found himself flung backwards hitting his head heavily on the ground. Then it was gone.

Struggling panic-stricken to his feet, the artist realized that his canvas was now quite destroyed. It too had smashed down hard, and an unknown soldier’s skull had ripped through the centre. The account is given in Opren’s book An Onlooker in France 1917-1919 (1921,2008)

However, here psychological and social pressures rather than ghostly ones may have been at work with these experiences rather than paranormal ones, with this being a personal rationalisation of a sudden collapse of nerves. Officers suffered war neurosis more frequently than the lower ranks, from having to suppress their own emotions as an example for their men. Dubbed “shell shock”, it would not have been good form to admit such a nervous collapse, since it was often diagnosed as a form of hysteria, then considered a predominantly female complaint. For Wheatley, so soon after being in battle, the experience of being alone under the moonlit and war ravaged landscape might have triggered the release of pent up fear and trauma. However, rather than admit this, it may have been much preferable to blame an external entity, one of the ‘elementals’ which featured frequently from 1934 onwards in Wheatley’s series of black magic novels and in which he readily believed. Similarly, Opren being of a creative and sensitive artistic temperament may simply have found his rational self overwhelmed and suffered a strange physiological reaction as a result which he did not understand.

Indeed, the fear that reporting a paranormal experience might be interpreted as a symptom of mental imbalance may be a factor to explaining why relatively few ghostly experiences were recorded by servicemen at the actual time on or around the battlefields. Such concerns certainly appear in some accounts published in memoirs years afterwards.

Poet Robert Graves (1895-1985) who saw ghosts on the Western Front and at home

On an individual level daily exposure to the risk of sudden death and the appalling toll in casualties made many servicemen and women highly superstitious, prone to ‘believing in signs of the most trivial nature” as admitted by poet Robert Graves in his classic Goodbye To All That (1929). Early in the War a password used by British soldiers in the trenches was ‘ghosts’ (see The Star 22 June 1951) and Graves recalled his own sighting of the phantom of a Private Challoner of the Royal Welch at Bethune in June 1915, whilst he was dining with comrades on ‘new potatoes, fish, green peas, mutton chops, strawberries and cream and three bottles of Pommard.” Graves suddenly saw Pte Challoner looking in the window of their billet, salute them and move on. Jumping up and looking outside Graves saw nothing but a smoking cigarette butt. “I could not mistake him or the cap badge he wore; yet no Royal Welch battalion was billeted within miles of Bethune at the time”. Challoner had been killed at Festubert in May 1915, having previously told Graves “I’ll see you in France, sir” before they had left England.

However, this incident did not disturb Graves anything as much as his experience on leave at Harlech in Wales when staying with a grieving woman whose son had been killed in France. She had left his room unchanged as a shrine in his memory, with linen regularly laundered and fresh flowers and cigarettes placed by the bed. After talking until late with an army comrade, Graves recorded that on retiring to bed he was continually awakened by raps, getting louder and louder which seemed to come from everywhere, and then by shrieks of a maid suffering hysterics. “In the morning I told my friend “I’m leaving this place. It’s worse than France””. This sounds like an outbreak of poltergeist phenomena but Graves attributed such manifestations to the dabbling of his hostess who along with “thousands of mothers like her…[was] getting in touch with their dead sons by various spiritualistic means”.

Thiepval Memorial to British and Commonwealth Dead. R.I.P.